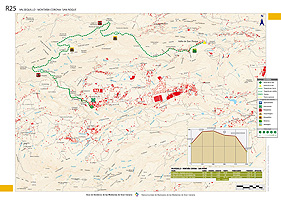

Valsequillo - El Helechal - San Roque

GENERAL DESCRIPTION. The trail runs through the lower end of the municipality, towards San Roque, where the municipality of Valsequillo borders Telde. In fact, the border line runs exactly through the centre of the church of San Roque, so the villagers would humorously say that the priest got dressed in Valsequillo to say the mass in Telde. The original chapel of San Roque dates from 1728, but only the presbytery and the vestry, of mudéjar style, have survived.

The trail runs through a landscape characterized by extensive human intervention: fertile farming terraces climb up the sides of the ravine to the point that they seem to be hanging over an abyss.

The church square, Plaza de San Miguel, where our trail starts, is located on the site of a prehispanic almogarén, or sacred site of worship. The church houses some first rate works of art. Our itinerary then runs up the Montaña del Helechal, a large phonolitic neck dating from the end of the Roque Nublo cycle, which offers the best panoramic views of the municipality. Its privileged location, practically in the centre of the municipality, have led some to believe it might have had some magic or religious significance for prehispanic Canarians.

The first stage in our walk coincides with the former way communicating Telde and San Mateo, which is why its initial stretch, from the village of Valsequillo to Lomo de Correa, is cobbled.

Along this route there is a predominance of basaltic, basanitic and nephritic lavas, as well as Roque Nublo volcanic breccias. The fertile farmlands around El Helechal and the lowlands of Valsequillo and Las Vegas lie on basanitic-nephelinic lava flows.

Spectacular vistas over the Caldera de Tenteniguada will open up before us as we walk up the Lomo de Correa hill ridge. Almost the whole of the municipality of Valsequillo can be seen from its crest, from the Barranco de San Miguel ravine to Los Mocanes; from Las Vegas to El Rincón, as well as the extensive lowlands of Valsequillo and El Montañón.

Traditional land use was mainly associated with shepherding and agricultural activity. The trail runs past several cave-sheds where the old mangers can still be seen. It is interesting to turn and look back to see the surprising number of cavities we have walked past on our way.

We will also come across an important number of cave-dwellings along the middle stages of the trail and when we arrive at San Roque.

The importance of farming in this area is reflected in the countless terraces we find along the way. It looks as if there is not one square metre that has not been cultivated. This extensive use of the territory is connected with the famine that affected the local population after the end of the Spanish Civil War, when the little food that came from outside was not enough to feed local families.

The importance of farming in this area is reflected in the countless terraces we find along the way. It looks as if there is not one square metre that has not been cultivated. This extensive use of the territory is connected with the famine that affected the local population after the end of the Spanish Civil War, when the little food that came from outside was not enough to feed local families.

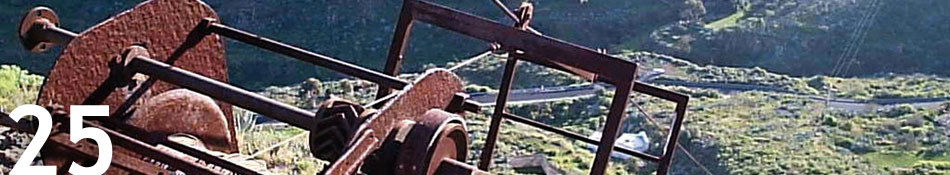

As we come to the end of the first stage we'll start leaving population nuclei behind. Farmers had to find a way of transporting their crops swiftly down to the main means of communication. They found the solution in manual and motor cranes of simple design: a strong metal cable was stretched between two masts and a trolley was used to carry potatoes, fruit and vegetables from one end to the other. In the last stage of our itinerary, at the southern end of the small basin of El Palmito, if we look towards the Barranco de San Roque ravine, we'll be able to see one of these devices designed to bridge the distance between this slope and the road connecting Valle de San Roque and Valsequillo.

This area's climate is fairly uniform, as there is hardly any elevation gain or loss involved between our starting and finishing points. Even so, the climate here is drier and warmer than in the higher middle mountain areas of Valsequillo.

The most common species that we'll come across are century plants, prickly pear cacti, wild olive trees (Olea europaea ssp. cerassiformis), white weeping brooms (Retama monosperma) and buglosses (Echium decaisnei), although the palm forest at San Roque (Phoenix canariensis) is worth highlighting, as it delightfully combines the slenderness of the Canary Island date palm with a natural environment that has been extensively modified by human intervention.

Trail description

Trail description

Stage 1: Valsequillo - Degollada de Lomo de Correa

This trail starts from the church in Valsequillo. We take León y Castillo street all the way to the end, where there is a scenic viewpoint that offers a panoramic view of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine. From there we carry on along the main road (GC-810) towards Montaña del Helechal (check the guide book for additional information), going up Sol street first, and then turning into del Majuelo street. Here, after about 75 metres, we take a path to the left and walk uphill past some houses towards a pine forest (Pinus canariensis).

This trail starts from the church in Valsequillo. We take León y Castillo street all the way to the end, where there is a scenic viewpoint that offers a panoramic view of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine. From there we carry on along the main road (GC-810) towards Montaña del Helechal (check the guide book for additional information), going up Sol street first, and then turning into del Majuelo street. Here, after about 75 metres, we take a path to the left and walk uphill past some houses towards a pine forest (Pinus canariensis).

We walk across the road, we walk up a path to the left of some pine trees amidst a thick shrub forest made up of white weeping brooms, prickly pear cacti, spurges (Euphorbia regis-jubae) and Montpelier rock roses (Cistus monspeliensis), among others. We walk past a water storage facility and come to a wide dirt track. A few metres into it we leave it, taking a path to the right that runs down a steep slope as far as the main road. After about 70 metres we take another path to the left that twists and turns up the eastern flank of the Montaña del Helechal. We follow the cobbled path until we once again get to the tarmacked road, along which we descend amidst farm fields where vegetables and fruit are grown, towards the northwest.

We carry on along this road, which after a straight stretch veers to the right and runs up a steep slope past some traditional style houses. We take a path that we find to our right that leads to Vega de San Mateo. We carry on, past a crossroads, until about 160 metres down the path we find another winding cobbled path that leads up to El Helechal. Once we have reached the top we can take a moment to enjoy the view of the Caldera de Tenteniguada towards the southwest.

Stage 2: Degollada de Lomo de Correa - Montaña de la Abejera Alta

We resume our walk and continue along this path -ignoring the turning at Degollada del Lomo de Correa- until we find a tarmacked track that runs towards the east(1), past a complex of cave-dwellings and sheds of ethnographic interest. We carry on down this track for about 1,250 metres, as far as a threshing floor that we'll see to the right. Past it we'll come to a crossroads, where we turn right into a turning that is signposted as private, but which only limits access to cars because it is a dead end(2).

We resume our walk and continue along this path -ignoring the turning at Degollada del Lomo de Correa- until we find a tarmacked track that runs towards the east(1), past a complex of cave-dwellings and sheds of ethnographic interest. We carry on down this track for about 1,250 metres, as far as a threshing floor that we'll see to the right. Past it we'll come to a crossroads, where we turn right into a turning that is signposted as private, but which only limits access to cars because it is a dead end(2).

Once we have gone past a pretty house set amidst farm fields we take another track (going over another chain) that will bring us to a eucalyptus tree (Eucalyptus camaldulensis), at the foot of which another narrow dirt path starts that runs amidst abandoned (but not too dilapidated) farming terraces.

The path narrows further after we reach the eastern slope of the Barranco Valle de Casares ravine. We border the slope and climb up to the crest of the interfluve between the Barranco Valle de Casares and the San Roque ravine to the south. If we look to the south we can see the lowlands of Llanos de Valsequillo and the different settlements in the municipality: Correa, Las Vegas, Era de Mota and the village of Valsequillo itself.

(1) If we went towards the west it would take us to San Mateo

(2) We should ignore all the turnings that lead into private properties along this stretch of trail.

Stage 3: Montaña de la Abejera Alta - San Roque

We walk across a terrace and climb up the mountain, practically to the top again; we carry on along its northeastern edge until we come to a shelf on the hillside, from where we descend down the other slope. Walking towards the west we twist and turn down a steep slope, across a small basin called El Palmito. The path keeps narrowing, and at stretches is hidden from view by the surrounding vegetation. It is easy to follow though, if we make sure we keep walking in the direction of the village of San Roque, which we can see towards the east.

We walk across a terrace and climb up the mountain, practically to the top again; we carry on along its northeastern edge until we come to a shelf on the hillside, from where we descend down the other slope. Walking towards the west we twist and turn down a steep slope, across a small basin called El Palmito. The path keeps narrowing, and at stretches is hidden from view by the surrounding vegetation. It is easy to follow though, if we make sure we keep walking in the direction of the village of San Roque, which we can see towards the east.

We come to an orchard at the foot of the slope, and walking towards the south we come to a concrete track that brings us, past some cultivated farm fields, to a tarmacked road. We follow this road and, once we have come to the end of Cuevas Negras street, we carry on walking on the left-hand side of the main road for about 1 kilometre approximately, in parallel to the exuberant palm forest of the Barranco de San Roque ravine, until we get to the village of San Roque, where our itinerary ends.

Montaña del Helechal

It is a large freestanding phonolitic rock dating from the end of the Roque Nublo cycle that acts like a natural border between two important fertile lowlands, the Llanos de Valsequillo and the El Helechal plains. Its central location meant it was regarded as sacred ground by prehispanic Canarians.

In the proximity of El Helechal, in the ravine known nowadays as "de San Miguel", the aboriginals led by Tecén offered fierce resistance to the invading Spaniards, engaging them in a bloody battle in defence of their almogarén, or sacred site. The site of the battle came to be known as Sepultura del Colmenar -Colmenar Sepulchre-, a name that has survived up to the present as there is a small hamlet called El Colmenar in the proximity of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine. Once they had conquered the area, the Spaniards placed their conquerors' cross on the summit of the Montaña del Helechal.

The presence of an almogarén meant that Montaña del Helechal possessed religious significance for prehispanic Canarians. Geographically, the spot was perfect, it was an elevated site of easy access from which the whole of the valley could be seen. The aboriginals held their religious rites here, where they worshipped their god Alcorán and the sun and the moon. Unfortunately, there is no trace left of this site, for at the beginning of the 1970s a restaurant-scenic viewpoint was built on it.

Today, this spot offers some of the best views of the east coast and High Mountain region of Gran Canaria.

The San Roque Palm Forest

Bordering the farm fields that lie on the slopes of the lower stretch of the Barranco de San Roque ravine, we come across the San Roque Palm Forest which, apart from its beauty and the fact that it confers an unmistakable identity to this corner of the municipality, plays an important role in the ecological workings of this area. It protects crops from dominant winds, it works as a border between fields and shelters many other species like wild olive trees (Olea europaea), sorrels (Rumex lunaria), prickly pear cacti (Opuntia ficus), berodes (different species belonging to the genus "Aeonium"), tamarisks (Tamarix canariensis) and century plants (Agave americana), as well as many animal species, mainly birds and invertebrates.

It is, additionally, an ecosystem where a native plant grows, the Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis). The Canary Island date palm has a number of characteristics that set it apart from other species, like its fruit, for instance, an oval orange-yellow drupe, known as támara. It reaches an average height of between 10 and 15 metres -on occasions some specimens can grow up to 25 metres tall- and its robust trunk is topped by numerous arched branches that can reach a length of up to 7 metres, forming a dense, spherical green crown. Palm leaves have traditionally been used as forage for animals and for the crafting of a range of domestic utensils, such as baskets, hats, brooms, etc, although at present the number of artisans who still practice this craft is extremely small.