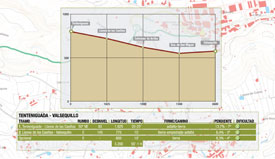

Tenteniguada - Valsequillo

GENERAL DESCRIPTION. The village of Tenteniguada lies inside the large erosion caldera of the same name, at about 800 metres above sea level, at the foot of the large freestanding rocks that crown the escarpments of the caldera. Its climate -typical of a middle mountain region- is characterized by hot summers and mild, relatively rainy winters. Its orientation towards the east prevents the sea of clouds caused by the trade winds from having more than an occasional effect on Tenteniguada, but humidity conditions are such that the landscape stays covered in a green mantle throughout the rainy season. It is an essentially agricultural area, producing mainly vegetables and a variety of fruit,. Among the latter, the most striking from a scenic point of view, are the almond, plum, cherry and chestnut trees.

Tenteniguada also boasts an architectural heritage of interest, like the church of San Juan(1), dating from 1916, and many dwelling houses of traditional style. It is certainly worth exploring the village, its little shops and picturesque alleys, like the del Cuerno or del Chorro streets, where we'll find beautiful examples of beautiful traditional Canarian stone-made houses with wonderful wooden balconies.

The Barranco de San Miguel ravine traverses the village, coming down from Valsequillo and running on towards Telde. The fertility of this valley favoured human settlement, and already shortly after the conquest people were moving up the valley and settling in Tenteniguada and Valsequillo.

The fact that the path that runs by the ravine was cobbled underlines the ethnographic importance of this area. It became necessary to ensure the passability of the path by cobbling it, as it was the main means of communication between the two most important villages in the municipality. In former times, beasts of burden would be led down the path loaded with baskets full of fruit and vegetables. They'd travel from El Rincón and Tenteniguada to Valsequillo, where the farmers' produce was transferred onto old lorries and taken to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. The oldest inhabitants of the municipality still remember how their parents -usually their fathers- would tell them that in their time they'd ride the whole way from Tenteniguada to Las Palmas, on a horse or on a donkey, setting off at dawn and not returning till dusk.

This path was also used to carry the deceased from the upper areas of the municipality down to the village of Valsequillo, where the cemetery was. This was the case until 1933, when the road and the bridge of San Miguel that connect Valsequillo with Temnteniguada were built. Curiously, the first "official" event associated with the new road was actually the funeral of an inhabitant of Tenteniguada. Even so, many people went on using the old path because it was shorter than the new road, except at times of rain or heavy storms.

Another feature of ethnographic interest in the valley was the first water mill(2)built on the slope of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine, at a time when there was a permanent flow of water. On the northern slope of the ravine, close to the village of Valsequillo, there is another historical architectural complex of great beauty: the cavalry barracks of El Colmenar, built in 1530, one of the most important elements of the architectural and historical heritage of the municipality.

The last stretch of our trail brings us to the old quarter of village of Valsequillo, where we should visit the church of San Miguel, built between 1903 and 1918 on a site formerly occupied by a cemetery. Inside we'll find some artistic jewels, like the figure of Saint Michael the Archangel (the only angel ever depicted with a dog at his feet, and carved by the renowned Canarian sculptor Luján Pérez), the green ceramic baptismal font, decorated rather grandly with a pair of eagles, fired in Seville in the 15th century, and an image of Our Lady of the Rosary, a Flemish figure dating from the time of the conquest.

(1) J. SUAREZ MARTEL records a curious anecdote about the church bell in Tenteniguada, SUAREZ MARTEL, J. (1996): Op. Cit.; p.59, which "was acquired in exchange for the remains of a broken bell and donations by the inhabitants of the village of Tenteniguada".

(2) According to SUAREZ MARTEL (1996): Op. Cit.; p 60, this water mill became the property of don Sebastián Pérez Macías, father of the renowned writer don Benito Pérez Galdós, in 1824.

Trail description

Trail description

Stage 1: Tenteniguada - Llanos de Las Casillas

The trail starts in La Parada street, which is the main street in the village of Tenteniguada. Before we get to a stand of pine trees (Pinus canariensis), we turn to the right and walk down San Juan street, past the church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, (built at the beginning of the 20th century in a traditional Canarian style, with façade features, pilasters and base made of stone work), and past a crossroads where we ignore a turning to the left. We carry on towards the east, along the northern slope of the Barranco de Tenteniguada ravine, amidst farms where fruit is grown and tall eucalyptus trees that border the road(3), with the Montaña del Helechal mountain ahead of us.

The trail starts in La Parada street, which is the main street in the village of Tenteniguada. Before we get to a stand of pine trees (Pinus canariensis), we turn to the right and walk down San Juan street, past the church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, (built at the beginning of the 20th century in a traditional Canarian style, with façade features, pilasters and base made of stone work), and past a crossroads where we ignore a turning to the left. We carry on towards the east, along the northern slope of the Barranco de Tenteniguada ravine, amidst farms where fruit is grown and tall eucalyptus trees that border the road(3), with the Montaña del Helechal mountain ahead of us.

The Tenteniguada palm forest is a delight: at a height of 700 metres above sea level, it is made up of a combination of palm trees and thermophilic species like the wild olive tree (Olea europaea), eucalypti (Eucaliptus camaldulensis) and almond trees (Prunus dulces). Past the palm forest we come to a curious hamlet with several dwellings of a traditional architectural style, many of which have been included in the municipal inventory of architectural heritage. The street comes to an end, where we take a dirt track that veers towards the southeast and then descends gently-at this stage the track is cobbled- down the northern slope of the Barranco de Tenteniguada ravine, where the first stage of this trail ends.

(3) Practically the whole of these lowlands (and wells and water galleries) belonged to a great landowner, don Juan del Río, and were farmed by local peasants up to the end of the 20th century, although today they are beginning to display a certain state of neglect.

Stage 2: Llanos de Las Casillas - Valsequillo

We walk down this cobbled track amidst spurges (Euphorbia regis-jubae) and century plants (Agave americana), as well as isolated specimens of eucalypti and wild olive trees; the increasing number of giant reed plants (Arundo donax) reveals the proximity of the ravine bed. At this point progress can be made a little difficult by the fluvial debris we'll encounter on our way.

We walk down this cobbled track amidst spurges (Euphorbia regis-jubae) and century plants (Agave americana), as well as isolated specimens of eucalypti and wild olive trees; the increasing number of giant reed plants (Arundo donax) reveals the proximity of the ravine bed. At this point progress can be made a little difficult by the fluvial debris we'll encounter on our way.

Once we get to the bottom of the ravine we'll take the old local road, which used to run past the water mill at El Colmenar -the oldest mill in Valsequillo- before reaching the village itself. However, after barely 15 metres we'll leave the road and we'll climb up a dirt track towards the hamlet of El Colmenar de Arriba. We carry on along a tarmacked road of about 600 metres in length, leave the mill house to our left, and walk across the road to take a path that we'll find right ahead of us. At the beginning of our descent we might have noticed the millrace down which the ravine's water flowed to turn the water wheel. Inside the mill there are still many of the implements and mechanisms that made it work.

We continue down the slope until we get to the bed of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine, but 120 metres down the bed we'll find another track that climbs up the ravine slope towards the northeast, towards the hamlet of El Colmenar, which we'll take. Before we get to the summit we should turn left and have a look at the El Colmenar cavalry barracks, a complex of former military facilities that are now used as rural tourist accommodation.

We continue walking up the slope, past some farm houses (some of them are cave-dwellings) and some fields where vegetables are grown, until we get to the road that leads to Tenteniguada. Here we should take a moment to admire the view of the ravine and of the hamlet we have just left behind. We cross over the road and carry on along the pedestrian street that lies on the other side, called Antonio Macías street. We walk on towards the centre of the village, where we'll find the square and church of San Miguel against a picturesque setting of neoclassical and Canarian traditional style houses, and of bars and cafés where we could sit down and quench our thirst. Our trail finishes here, but we'd recommend not leaving Valsequillo without first exploring it. It is worth bordering the church and walking up León y Castillo street to have a look at the façade of the Town Hall with its pretty Canarian style balcony, as well as the old quarter with the first few houses built in the village. At the end of the pedestrian street there is a small scenic viewpoint from which there is a great panoramic view of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine, the Caldera de Tenteniguada and El Rincón, all of them sites we have been to on our trail.

Our trail finishes here, but we'd recommend not leaving Valsequillo without first exploring it. It is worth bordering the church and walking up León y Castillo street to have a look at the façade of the Town Hall with its pretty Canarian style balcony, as well as the old quarter with the first few houses built in the village. At the end of the pedestrian street there is a small scenic viewpoint from which there is a great panoramic view of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine, the Caldera de Tenteniguada and El Rincón, all of them sites we have been to on our trail.

The Barranco de San Miguel ravine

The Barranco de San Miguel ravine is the main drainage channel of the Caldera de Tenteniguada, and it traverses the middle stretch of the Telde basin. Its course has cut across some old intracanyon lava flows. This old flow sectioned by the new drainage system formed lava terraces that were turned into farm fields by the local population, taking advantage of the quality of the soil and of the availability of permanent running water. In the past agricultural activity was primarily for self-consumption, and the most common crops were potatoes, vegetables and fruit. At present cash crops predominate, mostly strawberries and cut flowers.

The high scenic and floristic value of this ravine justifies its status as a protected space, and the diversity of its landscapes never fails to delight walkers. Its historical value is also significant. At the time of the conquest, the area known as El Colmenar was the site of a fierce battle between Spaniards and aboriginals led by Tecén. Cavalry barracks were built at El Colmenar as well, at the end of the 17th century. There are also prehispanic dwelling sites in the ravine, and old water mills that are vestiges of a time when water flowed permanently down its course.

Release of the Cursed Dog

The main festivities in the municipality of Valsequillo are held in honour of its patron saint, Saint Saint Michael the Archangel. The most popular festival is known as the Suelta del Perro Maldito, or the Release of the Cursed Dog, a tradition that in the past confined women and children to their homes because Satan, in the shape of a fierce dog, had managed to escape from Saint Michael's chain and a battle was now raging in the village between good and evil, freedom and repression, fear and pleasure. Men would go "hunting for witches and demons" in bars, and basically go out on a binge while their wives stayed at home.

For the last twenty years, a group of young people in the municipality have managed to revive this tradition, turning it into a street celebration for all. Thanks to them, every 28th November at night time the lights are turned off in the village and there is a magic outburst of fireworks, music, acrobatics and special effects.

The Suelta del Perro Maldito involves months of hard work, the object of which is to keep a tradition alive, involve the neighbours and make sure everyone, villagers and visitors, have fun on the night.