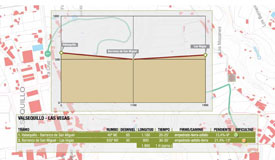

Valsequillo - Las Vegas

GENERAL DESCRIPTION. This trail connects two fertile lowlands of traditional agricultural character through a small path that traverses the Barranco de San Miguel ravine.

This is the path that used to connect both villages in the past, as the road that runs between Valsequillo and Las Vegas at present was not built until 1933. Before then, if the inhabitants of Las Vegas had to go to the doctor's, or go shopping, or wanted to get married, they had to walk down this narrow path to get to Valsequillo. Likewise, funeral processions had to traverse the same path, as the only cemetery was also found in the capital of the municipality. Once the road that linked the two villages across the San Miguel bridge was built, though, the path lost its importance. Even so, many villagers continued to use it for it took less time to get from one place to the other, and they also used it to get to Cho Vizcaíno's mill, to have the cereals they grew ground into gofio or flour. The path is 1,900 metres long, and it takes about 55 minutes to traverse.

It is not a difficult path, the slope is generally gentle, with a maximum gradient of 21º at some occasional points. Its surface is generally fine, and some stretches are cobbled, which is an interesting detail from an ethnographic point of view. The landscape the path traverses reveals the intimate relationship between the local inhabitants and the Barranco de San Miguel ravine.

The geological material we'll come across is varied. The whole area of the Caldera de Tenteniguada is characterized by large Roque Nublo cycle gravitational landslides, which covered the area occupied today by the caldera's interior space as far as Llanos de Valsequillo. During the Post-Roque Nublo cycle, these landslides were covered by basanitic and nephelitic lava flows, which is the material the villages of Las Vegas and Valsequillo lie on.

Both lowlands are traversed by the Barranco de San Miguel ravine, which geologically is the result of succesive periods of fluvial excavation. The work of erosion on the ravine walls reveals the old material, made up of gravitational landslide deposits. In the bed of the ravine itself we can see fluvial deposits.The predominant vegetation is typical of the dry thermocanarian layer, with species like bitter spurges (Euphorbia obtusifolia). The lowlands of Las Vegas and Valsequillo are some of the most productive farmlands of the Middle Mountain Region of Gran Canaria, due to the quality of their soil and their relative flatness.

The best time to take this walk is after the rainy season, when the water runs down the ravine. We'd realize then what a feat it was in former times for the local peasants to cross over their only means of communication, the Barranco de San Miguel ravine.

Trail description

Trail description

Stage 1: Valsequillo - Barranco de San Miguel

The trail starts at the Plaza de San Miguel square, in the centre of the village of Valsequillo. We turn in the direction of Telde, and about 300 metres down the road we'll find a petrol station and, next to it, El Calvario, a small contemporary religious construction that replaced the original one, which dated from the end of the 19th century.

The trail starts at the Plaza de San Miguel square, in the centre of the village of Valsequillo. We turn in the direction of Telde, and about 300 metres down the road we'll find a petrol station and, next to it, El Calvario, a small contemporary religious construction that replaced the original one, which dated from the end of the 19th century.

This building was originally larger and it had a roof, and its purpose was to offer visitors a welcome to the village. It also worked as a shelter and as a place of prayer, as it housed an image of Our Lady of Lourdes.

We take the turning that we'll find right opposite this small building.

The road comes to an end about 80 metres away further on, and we carry on along the path that follows from the road, past a round water tank to our left. We walk down to the ravine along this dirt path amidst relatively thick vegetation, made up mostly of bitter spurges (Euphorbia obtusifolia), berodes (Kleinia neriifolia), sow thistles (Sonchus leptocephalus), lavenders (Lavandula minutolii) and Canary Island sages (Salvia canariensis).

On our way down we'll see a well on the hillside to the right, with some of the implements used to extract water from the underground water table (a pulley, a bucket, etc) . We can also see the old Cho Vizcaíno's mill, which we'll get to once we arrive at the bed of the ravine. About 60 metres down the path we'll come to a crossroads, where we take the turning to the right, towards the south (210º).

At some points the surrounding vegetation hides the path from our view, but it is not difficult to follow it, winding along the gentle slope all the way down to the Barranco de San Miguel ravine bed. Some stretches of this path were cobbled by the local villagers, which is a feature of ethnographic interest.

The vegetation on this sunny hillside tends to be small in size, and its variety increases as we approach the bottom of the ravine. In the bed of the ravine itself we'll find a stone-wall dam, which was built by the Cabildo de Gran Canaria (the island's local government) as part of a recent project to repopulate the ravine with native species. These walls are designed to work like ditches, collecting water during the rainy season.

We take a dirt track towards the northeast (315º) that we'll find past the stone wall. If we are lucky we'll be able to see some buzzards (Buteo buteo ssp. insularum), We'll also see buglosses (Echium decaisnei), sorrels (Rumex lunaria) and reeds (Arundo donax) and Canary Island wormwood (Artemisia canariensis), among others. We can see on the sides of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine the old geological material that the process of fluvial erosion has brought to the surface; they are deposits of gravitational landslides that were later covered by basanitic-nephelitic lava flows belonging to the Post-Roque Nublo cycle. That's why it is possible to observe a difference in the granularity of the materials that make up the sides of the ravine.

At about 300 metres we'll come to a second stone dam and, past it, about 80 metres further down, we'll come to a mill, known as El Laderón or de Cho Vizcaíno. It is an interesting sight, even if it is in a poor state of preservation.

Stage 2: Barranco de San Miguel - Las Vegas

We walk about 15 metres back on ourselves from the mill, and take a path towards the south east (130º) that starts by four large rocks that lie on the bed of the ravine itself.

We walk about 15 metres back on ourselves from the mill, and take a path towards the south east (130º) that starts by four large rocks that lie on the bed of the ravine itself.

Again, the surrounding vegetation hides the initial stretch of the path, but as we follow it we'll realize this poses no difficulties as long as we ignore all the shortcuts leading off it that we'll encounter.

We veer towards the southwest (210º) climbing up a relatively steep slope (13º). The presence of debris and the slippery character of the terrain (if it has been raining) might demand a little effort on our part. Near the top of the hillside we should follow the direction marked by the wooden electricity poles. From here we have a wide panoramic view of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine, of the small hamlet of El Colmenar and of the village of Valsequillo.

At the top of the hillside we'll find a crossroads; right opposite us we'll see a stone wall and, next to it, we'll see a gently sloping path (10º) that runs towards the south (180º) and which will bring us to the village of Las Vegas. The path runs amidst farm fields where generally products typically produced in the Middle Mountain Region are grown, like potatoes, corn, green beans, courgettes and carrots.

After about 250 metres we'll find three centenary pine trees standing in front of a few houses; here there is a winery where one of the best wines in the municipality is made. A few metres further on we come to Las Moranas street, and barely another 150 metres on towards the east we'll get to the main road (C-814), which will bring us to the village of Las Vegas.

Optional stretch of trail - Los Mocanes

If we are feeling energetic enough to go on exploring this charming agricultural settlement, we recommend the following itinerary.

250 metres down from the end of Las Moranas street, and following the C-814 main road towards the centre of the village, we take a turning to the left by the Casa de la Cultura (House of Culture), and carry on down Las Suertecillas street. Along this stretch we'll see countless small farm fields where the villagers grow their crops.

900 metres from here we'll come to a palm tree standing in the middle of a small roundabout, where we should go up Las Haciendas street, towards the south west. After about 300 metres up a gentle slope we'll see an impressive private country estate, La Hacienda de Los Mocanes, over to our left. This is where our additional optional stretch of trail ends, so we'll return to the centre of Las Vegas the same way we have come. The best time to come along this stretch is between January and March, for that's when almond trees are in bloom. Likewise, in spring the hillsides of Los Mocanes ravine are filled with the yellow and white colours of the blossoming Canary Island brooms (Teline microphylla) and the particularly fragrant white weeping brooms (Retama monosperma).

The harvesting of almonds

We will have noticed the abundance of almond trees (Prunus dulces) along the trail. It used to be a crop of commercial importance in the past, and the harvesting of almonds was a curious process that merits description. First, after tasting the nuts and identifying the trees that produced bitter almonds in order to avoid them, the vareadores or pole-holders would knock the almonds down from the trees with poles or canes. They were then gathered in and, once back home, the women of the village would split the almonds open with stones and hammers to remove the shell. The quantities of almonds were such that the larger farms, like the Las Haciendas or del Jardín estates, would hire women and youths to do this job. In the 1960s, the first machine to shell and crack almonds arrived in Las Vegas -the first in the municipality, although there was already such a machine in Tejeda and another one in Tirajana-, and it belonged to don Jacinto Hernández. This machine, which is still preserved, made an unbearable noise while shelling and cracking sackfuls of almonds in very little time.

Almonds were eaten at home, used to make delicious typical confectionary or sold outside the municipality. In Valsequillo, the Almond Tree in Bloom Festival is held in February.

Threshing

Threshing is a traditional agricultural activity that involves beating the stems or husks of cereal plants to separate the grain or seed from the straw. The lack of machinery in the countryside meant that threshing was often done by the peasants themselves. The older villagers remember the threshing time as one of the most important moments in the year, since all members of the family and many neighbours as well took part in it one way or another.

The process was simple and slow, but emotionally charged as it was the result of long months of hard work. Cereals (wheat, barley, oats, rye, etc), sown months before, were first harvested, which was done by hand, using a sickle; they were then gathered and taken to the threshing floor, which were normally circular cobbled surfaces in the open air, deliberately located at breezy spots, generally on ridges or hillocks.

The threshing floors were often far removed from the farm fields or dwellings, so it was not uncommon for threshing to involve the family and neighbours having to take a packed lunch with them, or the necessary cooking items and ingredients to cook a meal on a logfire. While men organized the threshing, spreading the cereals over the threshing floor with the use of a winnowing fork, women would prepare the meal.

A team of cows or mules would trot round the circular perimeter of the threshing floor, and their trampling and weight would separate the grain from the straw. Often a thresher was used; this was normally a thick piece of chestnut timber studded with cutting stones that was attached to the yoke. People would stand on it, usually children, to increase its weight. As it moved in circles over the cereals the cutting stones would cut and tear off the straw, the seeds staying untouched between the thresher and the pebbles with which the threshing floor was cobbled. Once the threshing was over, the whole family would help to complete the process.

With the winnowing fork the straw was thrown up into the air mixed with the grain, and the wind would blow the lighter straw a few metres away, but the heavier grain would fall back onto the threshing floor.

Once the winnowing was over, the grain was collected into sacks, which were taken home; part of it would be kept for sowing again and part was ground -at home or at a water mill- to make flour or gofio. Straw was kept in sheds or straw lofts as forage for livestock.