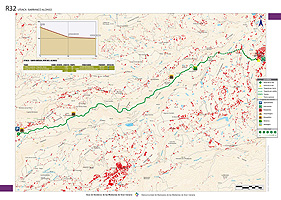

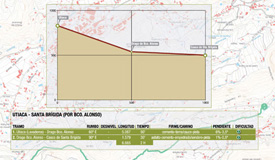

Utiaca - Barranco Alonso

GENERAL DESCRIPTION. This itinerary goes from Utiaca to the Barranco Alonso ravine, ending in Villa de Santa Brígida. The whole trail runs downhill to the bed of the ravine. Along the trail we'll be able to see peculiar geological forms and experience a particular microclimate which is milder than the climate in the surrounding areas and which has given rise to a distinct fauna and flora, especially in terms of rupestral species. Rainfalls reach an average of 500 mm, typical of the Middle Mountain region, although there is a notable interannual variability, i.e. very dry years tend to alternate with very rainy ones. In winter there is a high degree of humidity within the ravine.

We leave the the Barranco de La Mina ravine(Las Lagunetas - Utiaca trail) and enter the Barranco Alonso ravine, which is where our trail runs along until it gets to the Guiniguada ravine (Puente de Las Meleguinas - Jardín Canario trail). The trail runs mostly along the bed of the ravine, between the hillsides of Lomo Espino and Hoya Bravo.

The landscape is essentially agricultural in character, with many small farms where vegetables and fruit are grown, mostly for family consumption. The natural vegetation is made up of shrubs like berodes, cardoons or giant sow thistles, and of tree species such as palm and dragon trees as well as -to a lesser extent- wild olive trees. There are also some non-native plants, like prickly pear cacti and century plants ; the former is a relic of the cochineal industry and the latter has traditionally been used to make string and ship cables.

The sound of birds and running water will accompany us throughout the trail. We'll come across hydraulic structures, such as irrigation pipes, water tanks, water inspection chambers, distribution basins and washing places. In some stretches we will also see vegetation associated with water, like watercress and water lentils.

On arriving at the Barranco Alonso ravine we are entering the Pino Santo Protected Landscape. There we'll see columnar basalt jointings of great geological interests. Indeed, the valley hillsides were configured by volcanic basaltic series II and III (Fuster et al, 1968). Flows of great thickness combined with very fluid lava that flowed down to the northeast coast of Gran Canaria. Later, towards the end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene, fluvial erosion modelled this area's present relief.

On arriving at the Barranco Alonso ravine we are entering the Pino Santo Protected Landscape. There we'll see columnar basalt jointings of great geological interests. Indeed, the valley hillsides were configured by volcanic basaltic series II and III (Fuster et al, 1968). Flows of great thickness combined with very fluid lava that flowed down to the northeast coast of Gran Canaria. Later, towards the end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene, fluvial erosion modelled this area's present relief.

The trail starts at the Utiaca washing place, which we'll find by the bridge over the Barranco de La Mina ravine. We get to our trail's starting point via the San Mateo - Teror road. There is a parking area near the washing place, where we can leave our car.

Trail description

Trail description

Stage 1: Utiaca - Barranco Alonso

We leave the washing place and take the road in the direction of Vega de San Mateo. To the left we'll find a concrete path that runs down the hillside amidst small farms. We ignore a turning to the left and carry on along what soon becomes a cobbled path.

On both sides of the path there are some small posts whose function is to delimit maximum water levels in the ravine during the rainy season. The Consejo Insular de Aguas (The Island's Water Council) is responsible for these posts. Throughout this initial stretch the vegetation is made up of thick reed beds in the bottom of the ravine and of prickly pear cacti on both sides of the path.

Stage 2: Barranco Alonso - Village of Santa Brígida

Once we reach the bottom of the ravine the path widens. This is a nice spot where to stop for a rest and enjoy both the landscape and the silence. Once we carry on we'll come to another washing place, where we should take a cobbled path that runs along the ravine bed. We must be careful here, for many of the stones are loose and it is easy to slip and fall. In any case, the murmur of water, the singing of birds and the vegetation around us make the effort worthwhile.

We leave the bed of the ravine and take a wide dirt path to the right with a vastly better ground surface. We come to some caves that seem to be inhabited. Cave dwellings in the Canary Islands date from prehispanic times; later shepherds and farmers reused them as animal enclosures, storerooms or indeed as homes. Many of them are still inhabited, as they enjoy excellent bioclimatic conditions inside.

We walk on, always ahead, without returning to the ravine bed. Eventually we descend again along a dirt path to the right, and when we come to the bottom of the ravine we have to keep to the left of the ravine bed. Along this stretch we must always follow the path that runs parallel to the left bank of the ravine bed.

This path will bring us to one of the most outstanding landmarks in Gran Canaria: the Barranco Alonso ravine dragon tree. This dragon tree was first described by Kunkel in 1972. It is one of the few wild specimens on the island, since given the spot where it stands -a steep rocky wall- it could not have been planted by anyone. It is believed to be over 210 years old.

From here on the trail continues along the tarmacked road to Los Silos (a stretch of about 850 metres). To the left of the road we'll find a path that runs across the ravine. This stretch of trail coincides with a stretch of the trail that leads to Teror, which is signposted with a sign that reads “pa'l Pino”. This same path will bring us to the village of Villa de Santa Brígida, where the church, the market or the Wine House, among other places, are worth visiting.

The Western Canary Kestrel (Falco tinunculus)

The Western Canary Kestrel is a diurnal bird of prey that inhabits open grounds. It is easy to see in Gran Canaria and easy to identify given its wingspan (70-80 cm) and its length from head to tail (about 34-38 cm). The male has a blue grey cap and tail, and it is chestnut brown with blackish spots on its upper side. The female is larger, and its colour is brown with some reddish brown horizontal streaks.

Its hunting technique is peculiar: it hovers in the air beating its wings and tail quickly, searching the ground below for prey -usually insects, but occasionally mice and reptiles as well. Its song is a strident "kik-kik-kik…or kii-kii-kii…", which can be heard when it feels threatened by predators or when courting. Unlike most birds of prey, it does not build its own nests, but it lays its eggs (4-6) in rocky hollows or in other birds' nests. It lays eggs during the months of April and May.

The Dragon tree

Its genus name, Dracaena, comes from the Greek word drakaina (female dragon).

The dragon tree is a non-arboreal species that grows in the Macaronesian region and in northern Africa, between 200 and 600 metres above sea level. It used to form part of thermophilic forests. The dragon tree has been a protected species since 1991, and since 2001 it has been included with A2 category in the Catalogue of Threatened Species of the Canary Islands.

There is a new species that was discovered in 1999 in the southwest of Gran Canaria, known as Dracaena tamaranae. Its leaves set it apart: they have sharply pointed ends, their surface is grooved and grey-green in colour; and its inflorescence consists of three flower-bearing ramifications, rather than two, as is the case with the dragon tree specimens that had been known until then. Both species, Dracaena tamaranae and Dracaena draco grow in the wild, but specimens of the latter species are more commonly used in parks and gardens.

Dragon trees can live for a long time, and there are specimens that are centuries old. Their slow growth can be determined by the number of ramifications they display. According to some authors, there is a ramification every 15 years.

Phoenicians, Romans, people in the Middle Ages and prehispanic Canarians believed this plant had magic and mythical properties. They believed its sap, which once in contact with the air oxidizes and turns reddish in colour (dragon tree blood=dragon blood) was believed to have healing properties. Its sap was also formerly used to make dyes and varnishes, and was used for colouring paint and sealing wax, and to stop hemorrhages.