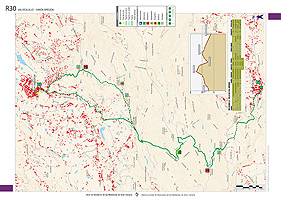

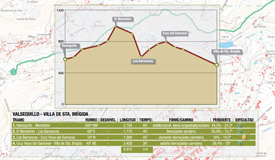

Valsequillo - Villa de Santa Brígida

GENERAL DESCRIPTION. This trail traverses the west and north areas of Valsequillo and the south and east areas of Santa Brígida.

One of the main geographical features of this natural space is the Barranco de Las Goteras ravine, which runs through three municipalities, Telde, Valsequillo and Santa Brígida. In the municipality of Santa Brígida it runs along a stretch that goes past Caldereta del Lentiscal, la Caldera de Bandama and Pico de La Atalaya. The ravine is flanked by wide gently sloping hill ridges, although the ravine's interior walls are very abrupt, usually with a gradient of over 30º. There are many colluvial basins, which are the remains of old cinder cones. A large quantity of lapilli surged from these volcanic edifices which at present cover the top soil like a black veil. This fertile mantle of lava gravel has favoured the widespread presence of vineyards in this area.

Geologically, the area is characterized by the presence of acid materials. In an initial phase, relief was shaped by pyroclastic flows which settled on the base of the island between 14.5 and 9.6 million years ago. It is mostly unwelded pumice and soft tuff, which explains the abundance of manmade caves in the area of La Atalaya. The interfluves between ravines are made up of phonolitic lava, some of which are up to 300 metres thick. Slabs are extracted from this material, and there are several quarries in the area. During the period that went from 9.6 to 4.5 million years ago there were no significant eruptions; this meant that the area's relief was mainly modelled by erosive agents which partially hollowed out the valleys we see today. These materials also make up the miocenic terrace of Las Palmas. Between 4.5 and 3 million years ago we have another period of eruptions, when lava and agglomerate flows of the Roque Nublo series covered and filled valleys. This was again followed by a mostly quiet non-eruptive period when valleys and ravines were hollowed out by erosion, leaving some terraces made of harder material standing. Finally, between 2 million and 700,000 years ago, new lava flows filled valleys and ravines again; these have since then only been altered by fluvial holocene and present day erosion, which has modelled the relief characterized by gentle slopes that we can see today. Unlike the salic-type material of previous eruptions, the later eruptions produced basaltic material. Recent peaks, craters and cones, such as the Bandama complex (the result of a phreatomagamatic eruption), the Caldereta del Lentiscal and Montaña Los Lirios, belong to this later period of eruptions.

The protected spaces in this area are the Protected Landscape of Tafira, especially the sector bordering the Las Goteras ravine, with palm tree and wild olive tree groves and vineyards; and the Bandama Natural Monument, which can also be seen from our trail, especially from the main hill ridges, from which there are splendid views of the northeastern sector of the island.

The climate in this area can be described as a transitional climate between the arid desert climate of the coast and the mediterranean climate of the Middle Mountain Region. The average annual temperature is about 19ºC. rainfall rates range between 300 mm and 500 mm. The influence of trade winds is marginal, for altitude stops the sea of clouds from generating horizontal precipitation. Windward side areas are windier than those on the leeward side -a factor which has partly determined the distribution of the population.

Thermophilic forests are the dominant potential vegetation: wild olive and mastic trees and lentiscs, associated with basaltic soil plants such as euphorbiaceae and verodes (Kleinia neriifolia). This natural vegetation has been heavily modified by human intervention in the form of both agriculture and livestock farming. The forest gave way to farmland, initially in ravine beds. Where soil moisture conditions were better sugar cane was grown, which was a product for export; hillsides and ridges, on the other hand, were turned into grazing grounds and farm fields where cereals, legumes and some vegetables and fruit were grown for local consumption.

This situation did not change until the 17th century, when sugar cane plantations were replaced by vineyards. The latter were even more widespread then than at present, for they were planted not just in the area of Bandama, but also throughout a good part of the Barranco de Las Goteras ravine and its surrounding area. As farmland grew forest cover shrank, and likewise common land shrank to the benefit of private property and farmland. In the 18th century the landscape changed again, and vineyards were replaced by cochineal nopal cacti; carmine, a crimson-coloured dye, was produced from cochineal, and it thus became a profitable export item. During the 19th and 20th century vegetable and fruit plantations gradually took over, a situation that has remained unaltered until today. Livestock farming -mostly goats- is sometimes combined with agricultural production. Hotel-based tourism and day-trips to nearby sites have also contributed to the tourist development of this area. The proximity to the city of Las Palmas has played an important role to this effect, as well as in favouring the widespread suburban development of these rural areas.

Trail description

Trail description

Stage 1: Valsequillo - El Montañón

The trail starts off from the centre of the village of Valsequillo. We walk up León y Castillo street -opposite the village church- as far as a small scenic viewpoint which offers a panoramic view of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine. Once the pedestrian street comes to an end we carry on along the GC-810 road in the direction of Montaña del Helechal. After about 75 metres we take a shortcut to the left of the road, and walk up a path that runs past a few houses towards a pine grove (Pinus canariensis).

The trail starts off from the centre of the village of Valsequillo. We walk up León y Castillo street -opposite the village church- as far as a small scenic viewpoint which offers a panoramic view of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine. Once the pedestrian street comes to an end we carry on along the GC-810 road in the direction of Montaña del Helechal. After about 75 metres we take a shortcut to the left of the road, and walk up a path that runs past a few houses towards a pine grove (Pinus canariensis).

We cross the road once again and continue along a path that runs to the left of the pine grove amidst a thicket made up of white weeping brooms (Retama raetam), cochineal nopal cacti (Opuntia cochinillifera), spurges (Euphorbia regis-jubae) and rock roses (Cistus monspeliensis), among other species. We then walk past a water storage facility where a wide dirt track starts. We soon leave this track, taking a path to the right and walking up a steep slope we arrive at the road. We follow it for about 70 metres and we take another path to the left that twists and turns up the eastern hillside of Montaña del Helechal. We carry on up this cobbled track until we get to the tarmacked road again, along which we go down in a northeast direction amidst vegetable and fruit farms.

After a straight stretch the road turns to the right up a steep slope with examples of traditional architecture on both sides. We take a dirt track to the right that runs uphill in the direction of San Mateo. We carry on along it past a crossroads in a northwestern direction. About 160 metres further on, to the right, we take a cobbled winding path that climbs up to the top of El Helechal. This is a good spot where to have a rest and enjoy the view of the Caldera of Tenteniguada to the southwest.

Stage 2: El Montañón - Los Barrancos

RAfter a rest we resume our walk along the dirt track in the direction of San Mateo, in other words, towards the west, away from the coast of Telde. The views of the Valsequillo valley and of the municipality of Telde are spectacular. After about 500 metres we come to a fork near a house. We take the turning towards the east, i.e. towards Santa Brígida and the city of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria -from this spot there is an excellent view of the island's capital. The track runs down a gentle slope past some power poles. We soon leave it to take the path that runs along the hill ridge known as Lomo del Montañón, which offers us the view of the Guiniguada ravine (Santa Brígida), to one side and of the Barranco de San Miguel ravine (Valsequillo) to the other side. We carry on down the slope until we come near the remains of an old house. The regeneration of thermophilic forests -especially wild olives- is particularly evident here.

A few metres before joining the dirt track again there is a turning to the left that leads us into the head of the Barranco de la Cañada Honda ravine. We walk down a path that runs next to a ditch, keeping to the right-hand side of the Cañada Honda, as far as the bed of the ravine. We walk across it to its left-hand bank and head towards a power tower that we'll see ahead of us. We must not leave the path at any point, for the vegetation is rather thick and it would be easy to lose our way. This path eventually joins a concrete track at the stream bed of Los Barrancos.

Stage 3: Los Barrancos - Cruz del Gamonal

We follow this concrete track briefly, for almost immediately we'll see a sign next to a path that reads camino (path). We take this path -it runs parallel to the bed of the ravine- which will bring us to a dirt track that we'll follow ignoring all turnings as far as the Cruz del Gamonal crossroads, easily identified by three crosses that have been raised next to it.

Stage 4: Cruz del Gamonal - Santa Brígida

From here there are two possible options. The first one consists in taking the track we'll find opposite a nearby bar, which -if we ignore all turnings- will take us straight to Santa Brígida, next to the petrol station that lies immediately past the village centre if travelling in the Las Palmas de Gran Canaria - Vega de San Mateo direction.

The second option is to follow the road towards La Atalaya de Santa Brígida. After about 500 metres we'll walk past a water supply tank to the right. The road runs uphill now, and will bring us to the area known as Las Tres Piedras (The Three Stones), about 750 metres past the water tank. There are splendid views here of the village of Santa Brígida and the area of the Barranco Alonso ravine, so it might be worth taking a few photographs. We leave Las Tres Piedras and return to the main road. If we followed it we'd arrive at La Atalaya de Santa Brígida first and then at San Roque, on the border between Villa de Santa Brígida and Valsequillo. Instead of this, we suggest taking the dirt path that we'll find next to Las Tres Piedras and walk down the hillside, parallel to some eucalyptus trees, towards Villa de Santa Brígida. We descend -carefully, its condition is far from ideal- along a path that twists and turns downhill; it runs past a dry water ditch, a water tank and a Holly Oak (Quercus ilex). When we get to a level stretch we'll see a fence -the path runs parallel to it- on the other side of which we'll see wild olive trees and lentiscs. The path comes to an end at El Molino housing estate, next to a water tank. We are now in Santa Catalina de Siena street, formerly known as El Molino (the Mill), which will bring us to a lane called del Castaño Alto (Tall Chestnut Tree). We walk past a sign that reads Cementerio (cemetery) and when we get to the entrance of the cemetery we walk down the steps we'll find off it. This will get us to the main road that runs across the centre of the village of Santa Brígida. It will only take us a few minutes to get to the village church square from there.

Palm trees in the Canary Islands

There are several kinds of palm tree in the Canary Islands, among them the Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis), the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), the desert fan palm (Washigtonia filifera), and the royal palm tree (Roystonea regia). Only the Phoenix canariensis is native to the islands, the rest having been introduced at different times in history. The date palm was probably introduced at the time of the Phoenicians or Romans.

In Gran Canaria most palm tree groves and forests are made up of specimens that are the result of the natural crossing between Canary Island date and date palm trees; there are very few palm trees left that are a hundred percent native. The Canary Island date palm reaches an average height of 15 metres; its trunk is slenderer and its crown tighter than is the case with the date palm, and its fruit, an oval orange-yellow drupe, is known as támara; the date palm can be twice as tall as the Canary Island date palm, its trunk is thinner and its crown more open; its fruit is known simply as a date. Male and female flowers grow on different palm trees. Brown pods encase male flower clusters, female flowers are characterized by fructifying stalks.

Palm trees have traditionally been used as a source of food for both people and animals in the case of támaras and only for people in the case of dates. Their different parts are used for the crafting of a range of products; with their leaves mats, baskets, panniers, sweeping brooms, hats, ropes, some clothes, backpacks and fishing nets are made; baskets are also made with their rachis and beehives with their trunk. Wine, vinegar and palm syrup (known as guarapo) and brandy are made with their sap.

The larger palm tree forests grow in La Gomera and Gran Canaria. Watercourses, regardless of altitude, orientation or exposure, are their natural habitat, so it is not surprising to see them grow throughout the island.

Rural tourism

Principle III of the The Hague Declaration on Tourism states that "An unspoilt natural, cultural and human environment is a fundamental condition for the development of tourism. Moreover, rational management of tourism may contribute significantly to the protection and development of the physical environment and the cultural heritage, as well as to improving the quality of life".

In order to meet these objectives, the Declaration itself proposes measures such as informing tourists of the natural and cultural values of the places they visit, promoting the sustainable development of tourist areas, restricting access to certain sites if necessary, compiling an inventory of manmade and/or natural sites tourist sites of interest, encouraging the development of alternative forms of tourism and ensuring both national and international cooperation between the public and the private sector.

Responsible tourism is without doubt a fast growing demand segment. Thus, both public bodies and private companies have chosen to work with this new form of tourism and offer specific high-quality products with a low natural or cultural impact. It involves a low-density leisure activity in highly scenic environments, requiring both physical exercise and an appreciation of the natural and cultural heritage of the tourist destination.

The Middle Mountain Region of Gran Canaria is ideally suited to meet this demand, and given the excellent range of accommodation in this area, rural tourism promises to become a thriving economic sector over the next few years.