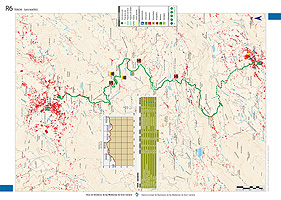

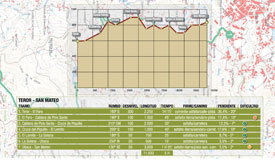

Teror - San Mateo

GENERAL DESCRIPTION. This itinerary runs between the villages of Teror and San Mateo.

The landscape the trail goes through is typical of the windward middle mountain region of Gran Canaria. The combination of abundant rainfall -about 800mm a year on average, distributed over winter, spring and autumn-, horizontal precipitations caused by the sea of clouds generated by the trade winds and the presence of thick soils rich in organic matter, favoured in the past the growth of a moist thick forest, a combination of laurel species and myrica-erica shrub forest known as monteverde, but over time forestland shrank considerably due to human intervention in the form of sugar mills, house-building and agriculture. With the virtual disappearance of the laurel forest from this area, rainfall volume has also dropped. Temperatures are mild and cool in winter (between 12º and 15ºC) and summers are slightly warmer now, between 25º and 30ºC, occasionally reaching over 35ºC when a thermal invasion from the Sahara desert takes place (a phenomenon known locally as calima).

For the last eight million years there has been in Gran Canaria a predominance of old basaltic lavas (series II, Fuster et al, 1968)) and of agglomerates from the Roque Nublo and Pre-Roque Nublo series. This type of material has given rise to a radially shaped relief whose centre is in the High Mountain Region of the island, with deep ravines and high hill ridges that alternate in a consecutive fashion. Abundant erosive deposits have accumulated on the beds of these narrow, deep, steep-sided V-shaped ravines, and they have consequently become prime farm land, as is especially the case in the Barranco de Utiaca ravine. These geological characteristics and the abundant rainfall have also favoured the existence of water springs associated with fossil soils.

The Pino Santo Caldera is a geographical feature of great interest. The crater is the result of a volcanic explosion and the development of a subsidence caldera. The deposits derived from the slopes of the volcano make up a rich soil that favours the growing of vegetables.

The most interesting gorges and gullies are those of San Mateo, La Mina, Castillejos, Madrelagua and Teror. Likewise, the most interesting hill ridges are El Faro, Los Lomitos, Lomo Gallego, Lomo Piquillo and Lomo de Castillejos. The trail that connects Vega de San Mateo and Villa de Teror runs constantly up and down steep slopes.

Throughout the trail we'll come across a range of both nucleated and dispersed settlements, farmland where products are grown for local or self-consumption and widespread livestock farming.

Trail description

Trail description

Teror - San Mateo

This is the trail used by pilgrims when they travel from Vega de San Mateo to Teror on the 8th of September, when they celebrate the festivity of the Virgen del Pino (Our Lady of the Pine tree). It is an old cobbled path, though some stretches are now paved in tarmac or concrete. The path is physically demanding, as it runs constantly up and down steep slopes, so only fit walkers should consider it.

Stage 1: Teror - El Faro

The trail starts at plaza de Sintes (Sintes Square), right behind the basilica of Our Lady of the Pine tree, in the municipality of Teror. We walk towards the crossroads of El Álamo, next to a children's playground, where El Chorrito street starts, a tarmacked road that leads down towards the ravine.

The trail starts at plaza de Sintes (Sintes Square), right behind the basilica of Our Lady of the Pine tree, in the municipality of Teror. We walk towards the crossroads of El Álamo, next to a children's playground, where El Chorrito street starts, a tarmacked road that leads down towards the ravine.

At the end of this street we get to the paseo de Florián (Florián promenade), ignoring the turnings to the left and to the right that we find along the way. From this spot we can see the basilica, its dome and the auditorium to the left. When we get to the end of the promenade we carry on along La Ligüeña street, which will bring us to El Pedregal.

We'll soon come to a crossroads, where we follow the sigposts to Arbejales and El Faro. The walk becomes rather steep. We leave La Igualdad square to our right, where we'll see a small canteen of the same name. The climb will bring us to another crossroads, where we take an alley called La Era which leads down to the ravine. It is initially paved in concrete, but it soon becomes a dirt track with a slight gradient.

As we walk down towards the ravine we'll take the first turning to the left. Once we get to the bed of the ravine we walk across it and carry on up Cuesta Falcón, which will bring us to the hamlet of El Faro, at the pass that leads onto the next ravine. This path is marked with red paint, indicating the direction we should follow. The vegetation along this stretch is made up of monteverde and Canary Island St. John's wort, many Arabian peas and fennels. It takes about half an hour to get half way up Cuesta Falcón.

At that point we leave the path and take a very steep concrete track. When we come to the first house we take another track to the right that leads to a tarmacked road. We carry on uphill and take the next turning to the left. Ahead of us, at the top of the hill, lies the hamlet of El Faro. We have to carry on along this tarmacked road, walking past all the turnings left and right. Half way up we'll find a cross next to the road, with an inscription (12-4-94) .

Once we get to a crossroads we walk on in the direction of El Faro. There is an old diesel-fuelled mill and a small village shop. In rural areas such as this it was not uncommon for people to have looms in their homes -there are some still left- for clothes were usually handmade.

To get to this point we have walked four kilometres in about an hour.

Stage 2: El Faro - Caldera de Pino Santo

When we get to El Faro, once we arrive at the houses located by the stream bed, we take the first turning to the right. We go down towards the ravine taking a path that runs past a house with a porch and a stone bench. The slope is rather steep, with a gradient of over 20º. We walk towards the southeast (140º), in the direction of Lomo de Enfrente. After crossing the bed of the ravine, just before we start our ascent, we'll find on a curve a fountain built in 1916, Fuente del Laurear, next to which there is a water trough.

We follow a track now that will take us to the Pino Santo Caldera. We walk past a house with a number 4 on its façade and past a water deposit. A few metres further on we come to a second water deposit and to a crossroads, where we take the turning to the right, in the direction of San Mateo.The path runs past the Pino Santo Caldera, affording a splendid view of this volcanic edifice and, if the day is clear enough, of the city of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and of the island's northeast.

Stage 3: Caldera de Pino Santo - Cruce del Piquillo

We leave the Caldera behind us and carry on along the road, past an irrigation channel and a water distribution basin, until we get to a crossroads from which we can see the village of Arbejales and the church of Sagrado Corazón de Jesús (Sacred Heart of Jesus). There we turn left, taking the road towards Lomo Gallego, in Vega de San Mateo, as far as a junction where secondary roads meet, at a spot with a few houses known as El Piquillo(1)), where the locally renowned family nicknamed “the tractor drivers” used to live.

(1) If we take the path to the right we'll get to Sagrado Corazón, Arbejales and Teror.

Stage 4: Cruce del Piquillo - Los Corraletes

We turn right and walk down a very steep concrete path with Villa de Santa Brígida right ahead of us, towards the SE, as far as a fork, where we turn right. On the outskirts of the hamlet of El Lomito, there is a basketball court; we have to walk past this court to get to the next gorge, called La Solana.

It will have taken us about three hours to reach this point.

Stage 5: Los Corraletes - La Solana

After a while we come to spot where there is an old rural school building to the left, a road that cuts across our path and opposite us, an orange house next to which the path starts to run downhill. This is known as Los Corraletes. We walk down to the bed of the ravine, cross it and walk up the slope towards the village of La Solana. Once we get to the village we take the first turning to the right. We walk past a corner shop and a bit further up we come to the village school and, next to it, a small square dedicated to Juan Esteban Alonso Navarro, a village neighbour. We carry on walking up the general road until we come to a turning to the left that will take us to Utiaca.

Stage 6: La Solana - Utiaca

Along this stretch of trail we see citrus and potato plantations that spread out onto the bed of the Barranco de La Mina gorge. We walk past a cattle farm and a house with a high wall and metal sheets as part of its roof. About 30 metres past this house, to our left, a path starts off that runs to the bottom of the gorge and passes near an old mill and the area known as Las Haciendas.

Stage 7: Utiaca -San Mateo

We walk across the bed of the ravine and carry on uphill following a dirt track that runs past a shed. We'll eventually get to a main road, following which we'll get to the village of San Mateo. Before we come to the San Mateo-Tejeda-Teror crossroads we'll find a restaurant with two side towers and a carpark. Opposite this establishment we take a track that leads to the Virgen de la Inmaculada Chapel (Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception). Once there we walk up Lourdes street, which will bring us to the back of the church of San Mateo. We walk round it and stop by its façade, where we come to the end of our walk, 11 kilometres and some five hours after setting off.

We walk across the bed of the ravine and carry on uphill following a dirt track that runs past a shed. We'll eventually get to a main road, following which we'll get to the village of San Mateo. Before we come to the San Mateo-Tejeda-Teror crossroads we'll find a restaurant with two side towers and a carpark. Opposite this establishment we take a track that leads to the Virgen de la Inmaculada Chapel (Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception). Once there we walk up Lourdes street, which will bring us to the back of the church of San Mateo. We walk round it and stop by its façade, where we come to the end of our walk, 11 kilometres and some five hours after setting off.

Traditional rural houses

Traditional rural architecture in the Canary Islands is one of the most significant elements of our cultural heritage. Each island has its own distinct type of popular architecture, which is the result of external influences (from southern Portugal, Extremadura, Andalusia and Castile) on the one hand, and natural conditions on the other, as even within a single island there are several very different ecosystems and environments. Houses on a humid mountainous island such as La Palma are inevitably different from houses on a low altitude flat island such as Fuerteventura.

On Gran Canaria alone, traditional rural homes on the island's humid windward region are different from those on its arid leeward side. Social distinctions also determined architectural differences - landowners' homes were very different from poor peasant dwellings.

The ornamental features of rural houses in Vega de San Mateo are wooden balconies, few and small openings and tiled roofs. They are usually built from stone and clay soil mortar, and then plastered with black lime, painted in ochre or simply whitewashed. Guillotine windows are frequent. As regards the interior, the floors are usually wooden or made of concrete; the ceilings have architraves made from heartwood and there are few rooms, except in the case of statelier homes.

Houses played an important role in rural life, as most activities took place there or in their proximity. Animal enclosures were not far, granaries to store grain and other produce were often located on the ground floor, next to the kitchen and the bathroom -if they existed. The poorest homes were made up of a single room, with washing and cooking facilities lying outside by the animal enclosures.

At present there are many abandoned rural homes, in varying states of neglect, although given the growth of rural tourism in Vega de San Mateo some valuable properties are now undergoing renovation.

Canarian spinning and weavers

After the sheep were shorn, the fleece was washed and dried. The fibres were then dyed and carded. The carded fibres were then spun into a yarn using either a spindle or a distaff. From this moment on the wool was ready to be used in making clothes, which was traditionally done with two needles. It was mostly in the higher middle mountain and high mountain regions that this activity took place, where shepherd blankets, waistcoats, hats and even jackets were made.

At present this traditional craft has practically disappeared, both because of the drop in the number of sheep and because of the import of cheaper and better quality wool from elsewhere, as well as because of the general trend towards buying manufactured clothes.

Textiles were woven on looms from the very moment the Spanish conquest took place. It was difficult and expensive to bring textiles from outside the island, and consequently looms became an essential tool for Canarian families.

From the 17th to well into the 19th century weaving was a widespread activity, whose significance only declined with the arrival of manufactured textiles produced in the industrial mills of Great Britain and of the Spanish mainland, especially of Catalonia. After the 1950s traditional looms became museum pieces, as Canarian society turned to cheaper imports and manufactured clothes.

It was mostly women who worked on looms, and it was an important complement to the economy of families in rural areas. The basic tool was the loom, together with the warper, the spool, the reel, purls, the espadilla (a threshing implement) and the shuttles. The raw material used was usually sheep and -to a lesser extent- camel wool, silk, linen and cotton.

One of the most curious woven fabrics were the traperas (scraps of cloth), made with leftover threads and used to craft mostly bedspreads and rugs. Textiles were dyed using natural products (orchil, cochineal, saffron, almond shells, onion skins, indigo and so on). This could be done before, but was usually done after the fabric had been woven.

(SOURCE: http://www.fedac.org)