Cueva Grande - Los Manantiales - Cueva Grande

GENERAL DESCRIPTION. This area is characterized by water collecting infrastructures that are uncommon throughout the rest of Gran Canaria, involving the exploitation of water springs and the use of caves as water deposits. Spring waters were channelled towards coastal areas, where the majority of the population had settled and where the main export crops, tomatoes and bananas, were grown.

The geological composition of this area is essentially made up of Roque Nublo material, above all agglomerates, although between the successive flows and eruption phases different layers of soil were formed and then compacted and burnt, giving rise to paleosols or fossil soils. These compacted fossil soils provide a watertight layer that stops water that has leaked through Roque Nublo complex fissures from leaking down any further, and the water accumulated eventually surfaces again in the form of water springs at those points where the fossil soil meets an upper layer of lava flow. This water is first collected in water deposits and then sent via canals or irrigation ditches to the usual areas of consumption.

The abundance of brooms, false brooms and flatpods once supported both free-range and stabled livestock farming, as the large number of now abandoned sheds and enclosures show.

Most of the forests we'll see along the walk are the result of reforestation programmes. We'll see some chestnut and walnut trees and some white poplars as well, but the bulk of the vegetation is made up of brooms and flatpods. The abundance of abandoned farming terraces in this area of Los Manantiales, especially those further removed from population nuclei, have favoured shrubland expansion.

Cold winter temperatures in combination with the trade winds generate a sea of clouds that is virtually a permanent -and stunning- seasonal feature at Cueva Grande.

Trail description

Trail description

Cueva Grande - Los Manantiales - Cueva Grande

The description of this trail is dedicated to don Estebita González, a neighbour of Cueva Grande, for his help was invaluable in getting to know this area in general and this trail in particular.

The description of this trail is dedicated to don Estebita González, a neighbour of Cueva Grande, for his help was invaluable in getting to know this area in general and this trail in particular.

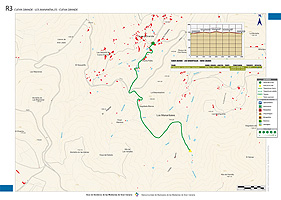

This is a circular walk, it starts and ends at Cueva Grande. The first stage, up to Los Manantiales, is uphill, with some light descents, and the return is along the same path, but mostly downhill. This trail runs past some of the most interesting hydraulic infrastructures in the High Mountain Region of Gran Canaria, such as water deposits excavated in paleosols, infiltration galleries and water transportation structures such as canals and irrigation ditches.

The trail starts at the village of Cueva Grande, on the curve where the former one-room schoolhouse lies, which at present houses the Neighbours' Association. We leave the main road and take the track that runs past the old school, towards the church of San Juan Bautista (St. John the Baptist). There is a dirt track that starts opposite its façade. We walk up this path for a few metres, until we get to a concrete track that is flanked on its right-hand side by the Barranco del Burro ravine. This track will bring us to a curve on the main road (GC-600 ), just past the milestone that reads “Kilometre 3”.

We walk across the road and take the path that we find on the opposite side (photo below). This path used to be taken by local inhabitants to come with their animals from the High Mountain areas down to Cueva Grande and San Mateo. We'll be able to see a number of curves along which the animals would come down the mountain, while people would take narrower shortcuts in a straight line. We should never leave the wider general track, for this is the one that will take us straight to Los Manantiales.

Soon after the start we'll go past a chalet. The path will bring us to Degollada Blanca amidst brooms and flatpods, as well as Canary Island sages and white sages. Once we get to Degollada Blanca we'll be able to enjoy excellent views of Cueva Grande and of La Siberia to the north.

Soon after the start we'll go past a chalet. The path will bring us to Degollada Blanca amidst brooms and flatpods, as well as Canary Island sages and white sages. Once we get to Degollada Blanca we'll be able to enjoy excellent views of Cueva Grande and of La Siberia to the north.

We carry on in the direction of La Calderetilla -looking back every now and then, for on clear days the views deserve it-, and after that we turn towards Los Manantiales. On our way to Los Manantiales we'll go past some farming terraces and when we come to a fork we have to take the path to the left, for the one to the right leads to Corral de los Juncos via Montaña de La Arena.

In the area of La Calderetilla we'll come across some pylons raised by the British who purchased this land in the 19th century with the aim of supplying their coastal plantations with water. This land belongs at present to the Town Council of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and the area's water is exploited by EMALSA(1)). We'll also see many asphodels and morgallanas, as well as chestnut, pine and eucalyptus trees that were planted about 50 years ago.

We carry on and walk past some more farming terraces where formerly cereals, legumes, fruit (apples, chestnuts, walnuts, pears) and potatoes were grown. Higher up, between some terraces to our right, we'll see the house that used to belong to Manolito Quintana, a local farmer.

From this point on we'll start coming across the first water deposit-caves that collected water from Los Manantiales. Water was used for irrigation and for animal -never human- consumption. After walking past an enormous chestnut tree we'll enter an area known as Llano Blanco, where we take a path that goes down to the left. The turning right leads to Hoya del Salao- which would take us to La Veguerilla, an area with Canarian pine trees that are the result of reforestation programmes undertaken by the Town Council of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, owner of this land. High up in the High Mountain Region, towards the south, we can see Roque Redondo.

From this point on we'll start coming across the first water deposit-caves that collected water from Los Manantiales. Water was used for irrigation and for animal -never human- consumption. After walking past an enormous chestnut tree we'll enter an area known as Llano Blanco, where we take a path that goes down to the left. The turning right leads to Hoya del Salao- which would take us to La Veguerilla, an area with Canarian pine trees that are the result of reforestation programmes undertaken by the Town Council of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, owner of this land. High up in the High Mountain Region, towards the south, we can see Roque Redondo.

We now take a narrow path where we should be careful not to slip on the abundant pine needles that cover its surface. Once we get to the bed of the Barranquillo de Los Manantiales ravine, we should walk up its left flank. We'll see a black pipe and a covered water ditch. After a brief climb we get to Los Manantiales, where we'll find a water tank that on its upper side has a canal for runoff water and several openings in the ochre wall to facilitate water drainage. In this area we should watch out for stinging nettles.

We take the same path downhill, and as we get the the bed of the ravine again we walk up the path that leads to El Llanito, where we'll see an abandoned shed. Opposite, towards the High Mountain region, we can see Roque Redondo and beyond it Roque Margarita. This is where the path that leads to Camaretas starts off, but that is not our trail. After enjoying the views we return following the same path that brought us here, until we get back to Cueva Grande, where the trail ends.

(1) For further information, check the following work by ENCARNA GALVÁN GONZÁLEZ (1996): El Abastecimiento de Agua Potable a Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. 1800-1946. Consejo Insular de Aguas. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria

High mountain vegetation: Brooms and flatpods

This kind of vegetation is more characteristic of the islands of La Palma and Tenerife, given that both reach altitudes higher than 2,000 metres, but in the High Mountain region of Gran Canaria we can find broom (Te-line microphylla), flatpods (Adenocarpus foliolosus) and false brooms (Chamaecytisus proliferus), among other plants. These species adapt well to high thermal oscillations: high summer and low winter temperatures with scarce rainfall (under 500 mm) and the very occasional snowfall. These climatic conditions, together with the scarcity of soil or its poor quality have given rise to a stunted vegetation which, apart from the species above, also includes thymes (Genus Micromeria), Canary Island and Montpelier rock (Cistus symphytfolius and mompeliensis).

Many of these species make up the undergrowth in the pine forest. In former times Canarian cedar trees (Juniperus cedrus) must have been abundant, but demand for their wood by cabinet makers led to their extinction in Gran Canaria, unlike in La Palma and Tenerife, where there are still some specimens left in remote areas.

The crafting of traditional zurrones (leather bags or pouches)

The zurrón was an essential element in the life of the islands' shepherds, for in it they made their gofio mixture, known as pella, mixed with milk or water and, on occasions, broth. Sometimes cheese or nuts (almonds, raisins, etc) were added as well. It was also used to carry other food (traditionally called the conduto).

The crafting of zurrones gave rise to specialist artisans, the zurroneros, but with the decline in the number of shepherds they have also disappeared. The tools required to make a zurrón or leather bag were the following: the hide of a kid younger than one (ideally between a fortnight or a month old), salt to cure it, serum and wormwood oil, the Canarian knife to cut the leather, an awl, a deep container, a wooden spatula and a stick.

Zurrones were made in the following manner:

1.- The animal was killed -it was cut as high up as possible to ensure the widest opening for the bag.

2.- Air was introduced by means of a cane to separate the hide from the rest of the animal, and the kid was then skinned from the tail towards the neck, never cutting its stomach.

3.- Salt was added and it was left to cure for a week or two.

4.- Salt was shaken off the hide and then hair was carefully removed using dull blades. It was then submerged in milk for 24 hours and after that it was flattened with the spatula to make it softer and whiter.

5.- The hide was then dried in a cool, dry, closed space and sprinkled with gofio to stop it from going moldy and smelling badly.

The botijero or cajero, a kind of backpack, was simply a larger bag made with the hide of an adult goat.